How I Built a Production Notification System for TravelTimes in One Day with Claude Code

From 'users want commute alerts' to 1,800 lines of shipped, App Store-ready code in a single coding session. A deep dive into architecture, edge cases, and what AI-assisted iOS development actually looks like.

How I Built a Production Notification System for TravelTimes in One Day with Claude Code

From "users want commute alerts" to 1,800 lines of shipped, App Store-ready code in a single coding session.

The Problem That Started It All

TravelTimes is a personal iOS app I've maintained for over 10 years. It does one thing: shows you how long your commute will take, right now. You open the app, you see travel times for your saved routes, you leave.

Simple. Useful. And completely useless at 6:45 AM when you're pouring coffee and haven't opened the app yet.

The most requested feature since I launched v8.0.0 with iPad support was obvious: "Can it just... tell me? Before I leave?"

Notifications. Scheduled, recurring, per-route notifications that deliver fresh travel time data at the moments you actually need it. Before your morning commute, before you leave the office. Not push notifications from a server. Not a one-size-fits-all daily alert. Personalized, schedule-driven, locally-managed notifications tied to exactly the routes you care about.

This is not a trivial feature. It touches persistence, background refresh, thread safety, iOS notification APIs, permission flows, and a full CRUD interface. It lives at the intersection of several iOS subsystems, and historically it's the kind of feature I'd block out a week for.

I built it in a day with Claude Code and Opus 4.6. Here's how.

The Architecture Conversation

The first thing I did was not write code. I described the feature to Claude Code and we talked architecture.

I started a conversation with Claude Code using this prompt.

I started a conversation with Claude Code using this prompt.

What emerged was a clean separation of concerns: a dedicated data model to represent what a schedule is, a manager class to own all interactions with iOS's notification system, two full view controllers for the user interface, and targeted modifications to the existing persistence, networking, and app lifecycle layers.

The key architectural decision was giving each concern a single owner. One class owns notification scheduling. A separate class owns data persistence. Neither knows too much about the other. The notification engine asks the persistence layer for routes and schedules. The persistence layer tells the notification engine when data changes. Clean boundaries, minimal coupling.

The pipeline that holds it all together is straightforward in concept: every time fresh route data arrives (whether from a manual refresh, a pull-to-refresh, or a background fetch) the data gets cached, and then notifications are immediately re-scheduled with that current data. The user never sees stale information in a notification. That pipeline is the heartbeat of the entire feature.

The Data Model: Getting the Foundation Right

Good features start with good models. A notification schedule, at its core, is just seven pieces of information: a unique identifier, a list of route references, a set of days, an hour, a minute, an enabled flag, and a creation timestamp. That's it. But the design choices embedded in those seven properties ripple through the entire system.

References instead of copies. Schedules store route IDs, not full route objects. This was the single most important design decision. When fresh travel time data arrives from the network, we don't need to find and update every schedule that mentions a route. We just re-resolve those IDs against the latest data at the moment a notification fires. One decision, and an entire category of data consistency bugs simply can't exist.

Sets instead of bitmasks. Days of the week are represented as a set of enum values rather than a bitmask or ordered array. Checking whether a schedule includes Monday reads like plain English, and toggling a day in the UI is a one-line set insertion or removal. The enum's raw values align with the iOS calendar system, so converting a weekday into a notification trigger requires zero translation logic. The data model and the platform API speak the same language.

Domain knowledge baked into presets. Rather than forcing users to configure every new schedule from a blank slate, the model includes factory methods for common patterns: a morning commute preset (weekdays at 7:00 AM) and an evening commute preset (weekdays at 4:30 PM). Claude suggested these during our initial design conversation, recognizing that reducing friction at schedule creation time would be critical for adoption.

Smart display formatting as a first-class concern. The model itself knows how to describe its days in human-readable terms. If all five weekdays are selected, it says "Weekdays," not "Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri." Saturday and Sunday together become "Weekends." All seven become "Every day." These aren't cosmetic afterthoughts. They demonstrate how thinking about the user experience at the model layer produces cleaner UI code, because the view controllers don't need to reinvent that logic.

The Scheduling Engine and the 64-Notification Cap

The notification manager is where iOS-specific complexity lives. It's a singleton (appropriate here, because there's exactly one notification center per app) and it handles three responsibilities: managing permission requests, scheduling notification triggers, and responding when users interact with delivered notifications.

The most interesting aspect is how a single human-readable schedule becomes multiple system-level notification requests. iOS local notifications trigger on calendar date components: a weekday, an hour, and a minute. A schedule that says "weekdays at 7:00 AM" doesn't produce one notification. It produces five, one repeating trigger for each weekday. A user with both a morning and evening commute schedule is already at ten pending notification requests. The system fans out quickly.

This is where Claude Code caught a production issue I wouldn't have anticipated until real-world testing.

iOS imposes an internal limit on how many pending notification requests a single app can hold. Exceed that limit, and the system silently drops the overflow. No error. No callback. No delegate method. Notifications just stop firing. From the user's perspective, the app is broken, and there's no diagnostic breadcrumb to explain why.

We implemented a hard cap of 64 pending requests. The scheduling engine tracks how many requests it has registered and stops adding more once it hits the limit. The math works out generously for a commute app: nine schedules at seven days each produces 63 notifications, just under the wire. But the cap exists because without it, a power user who creates ten or more schedules would silently lose their oldest notifications. The kind of bug that generates one-star reviews saying "notifications randomly stopped working" with no reproducible steps for the developer.

This safeguard came from a follow-up commit, after Claude and I traced through the scheduling flow and asked ourselves: "What happens at scale?" The answer was "silent failure," so we fixed it before shipping.

Threading Data Forward (and the Stale Content Bug)

The persistence layer coordinates access between the main thread (where the UI lives), background refresh tasks (which iOS can wake at any time), and the notification engine (which reads and writes schedules as part of its re-scheduling flow). Three separate locks protect three separate domains: one for cached route data, one for the user's favorite routes, and one for notification schedules. Each lock is scoped to exactly one data type, which means concurrent operations on different data types don't block each other.

This is unglamorous code. It will never make a conference talk. But it's the code that prevents the app from crashing when a background refresh fires while the user is in the middle of editing a schedule. Two threads touching the same data at the same instant. The kind of race condition you'd never hit during development on a single device and would hit once a week in production with thousands of users.

The first version of the notification update flow had a subtle bug hiding in exactly this territory. When a background refresh completed, the system would fetch fresh routes from the network, save them to the cache, and then tell the notification engine to update its content. So far, so good. But the notification engine, when asked to update, would reach back into the persistence layer and load the user's favorite routes list, a separate data store from the route cache.

Here's the problem: the favorites list stores route objects as they existed when the user last opened that screen. The route cache stores whatever the network just returned. A route might show a 45-minute commute in the cache (fresh from the network five seconds ago) but still show a 30-minute commute in the favorites list (from yesterday afternoon). The notification would display yesterday's travel time.

The fix was surgical. Instead of having the notification engine re-read from persistence, we changed it to accept fresh route data as a parameter. The persistence layer, immediately after saving the fresh data, hands that same data directly to the notification engine. No round-trip through storage. No chance for the data to go stale between "I just saved this" and "now let me read it back."

This pattern shows up repeatedly in iOS development: the gap between "data you just fetched" and "data you read back from persistence" is where bugs hide. Two sources of truth, even briefly, create a window for inconsistency. The fix is always the same: thread the data forward instead of reading it back.

The UI: Full CRUD

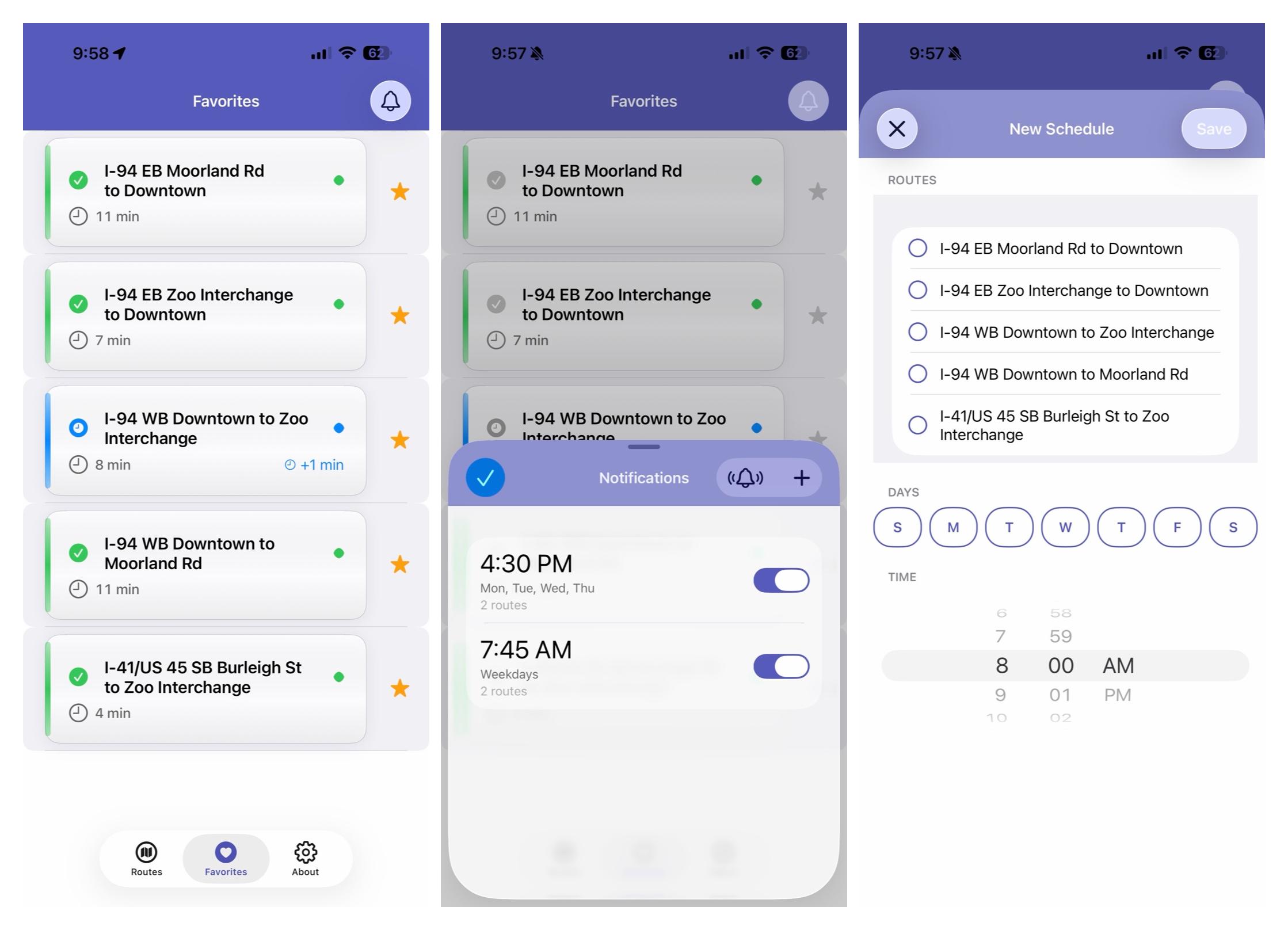

The notification feature needed two complete screens: a schedule list and a schedule editor.

The schedule list follows a familiar pattern elevated by small touches. Each schedule appears as a cell modeled after Apple's own Clock app alarm interface: a large time display, a secondary line summarizing which days are active, a tertiary line showing how many routes are included, and a toggle switch on the trailing edge for quick enable/disable. Toggle switches animate the cell's text opacity, so enabled schedules are fully opaque and disabled ones fade to half transparency. It's a subtle visual cue that communicates state at a glance without requiring the user to parse the toggle itself. Swipe-to-delete includes a confirmation dialog that names the specific schedule being removed ("This will stop notifications at 7:00 AM on Weekdays"), because destructive actions should always tell you exactly what you're about to destroy.

An empty state view appears when no schedules exist, complete with an explanatory message and a call-to-action button that navigates directly to the editor. The test notification button fires a sample notification after a five-second delay, giving the user time to background the app and see the banner in real conditions.

The editor is a scrollable form with three sections: route selection, day selection, and time selection. Route selection presents the user's favorite routes as a list with checkmark toggles. The day picker is a custom view: seven circular buttons arranged horizontally, each representing a day of the week. Selected days fill with the app's accent color; unselected days show as outlined rings. It's roughly a hundred lines of code that produces a component indistinguishable from something you'd find in a first-party Apple app. Time selection uses a standard date picker in wheel mode. Nothing custom needed. Sometimes the best UI decision is knowing when the platform's built-in component is already correct.

Validation happens at save time with specific error messages. "Please select at least one route" and "Please select at least one day" are two different prompts, because telling a user "invalid input" when you know exactly what's missing is a UX failure.

Every interactive element generates appropriate haptic feedback: light taps for selections and toggles, a medium pulse for saves, a success confirmation for deletions, and a warning bump for validation errors. Claude added these consistently across every action without being asked. It had internalized the existing haptic patterns from the codebase and applied them to every new interaction point by default. That kind of pattern recognition (reading hundreds of lines of existing code and extracting the implicit conventions) is where AI-assisted development adds real value.

Background Refresh: Keeping Notifications Current

The background refresh integration is what elevates this from a demo feature to a production system.

The app registers for periodic background refresh at a minimum interval of fifteen minutes. When iOS wakes the app silently in the background, a chain of events fires: the network layer fetches fresh travel times from the API, the persistence layer caches the response, and inside the save completion handler, the notification engine re-schedules every pending notification with the updated data.

This means a notification that fires at 7:00 AM on a Tuesday morning contains travel times that were refreshed within the last fifteen to thirty minutes, not the stale times from when the user last opened the app three days ago. The notification tells you what your commute looks like right now, which is the entire point.

A twenty-five-second timeout guard ensures the app doesn't get terminated by iOS for exceeding its background execution budget. If the network call doesn't complete in time, we cancel cleanly and let the next scheduled background refresh try again. Resilience without complexity.

Cleanup: When Favorites Change

One edge case that's easy to overlook: what happens when a user unfavorites a route that's included in one or more notification schedules?

The system handles this through cascading cleanup. Removing a favorite triggers a scan of all notification schedules. Any schedule that references the removed route has that route stripped from its list. If a schedule loses its last route (meaning it would fire notifications with no content) it's deleted entirely. The remaining schedules are then re-saved, which triggers a full re-schedule of all pending notifications.

A schedule monitoring routes A, B, and C that loses route B becomes a schedule monitoring routes A and C. A schedule that loses its only route disappears. The user is never left with phantom schedules pointing at routes they no longer care about, and no orphaned notifications fire with empty content.

Accessibility

Every element of the notification UI is fully accessible. VoiceOver labels on all interactive elements describe available actions ("Double tap to toggle," "Swipe left to delete"). Dynamic Type support ensures text scales with the user's preferred size. State-aware values communicate "Selected" or "Not selected," "Enabled" or "Disabled." Full contextual labels on schedule cells read as "Enabled notification at 7:00 AM, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, 3 routes."

This isn't accessibility as a checkbox exercise. It's woven into every configuration method and every UI setup function from the start. Claude Code treated accessibility as a first-class concern throughout the implementation, not as a cleanup pass after the "real work" was done. The cost of building it in from the beginning was negligible. The cost of retrofitting it later would have been substantial.

What Claude Code Actually Did

Let me be specific about the human-AI collaboration here, because the nuance matters.

I provided: The feature vision, the architectural constraints (programmatic UIKit, thread-safe persistence patterns, an existing design system), the quality bar (App Store submission ready, no unsafe unwraps, full accessibility), and code review at each step.

Claude Code provided: The implementation across roughly 1,800 new lines and modifications to four existing files. It followed the codebase's existing conventions: design tokens for colors and typography, the established haptic feedback utility, debug-only logging guards on every print statement. It caught the stale notification content bug during review, suggested the 64-notification cap as a safeguard, and built comprehensive accessibility support without being prompted.

The work landed in two commits: the initial feature implementation, and a targeted follow-up fix for the stale content and notification cap issues. That second commit is the telling one. It came from reviewing the first implementation and asking: "What are the edge cases?" The ability to iterate this quickly (implement, review, identify subtle bugs, fix) is where AI-assisted development changes the velocity of solo development.

Total new code: ~1,850 lines across 4 new files + modifications to 4 existing files. One coding session. Two commits. Zero unsafe unwraps. 100% accessibility coverage on interactive elements. Three dedicated thread safety locks. Platform edge cases handled: notification cap, stale content, orphaned schedules, permission denial.

Lessons Learned

Model design is leverage. The decision to reference routes by ID instead of embedding full route objects eliminated an entire category of data consistency bugs. Time spent getting the model right pays compound interest across every layer that touches it.

Thread your data forward. Don't fetch data, persist it, then read it back when you need it two function calls later. Pass it through. The stale content bug existed because the "read it back" path crossed a persistence boundary.

Respect platform limits. iOS's silent notification cap is poorly documented and devastating in practice. Always ask yourself: "What happens when the user does more of this than I expect?" If the answer is "silent failure," you have a bug, not a feature.

Accessibility isn't a feature, it's a quality attribute. Building it in from the start costs almost nothing. Bolting it on later costs a rewrite. Treat it like type safety: something you'd never consider adding "in a future sprint."

AI-assisted development is pair programming, not autopilot. I made every architectural decision. Claude executed with precision, consistency, and an awareness of the existing codebase that would take a human pair programmer days to develop. The best results came from clear constraints and iterative review, not from handing over a vague prompt and hoping for the best.

The notification system shipped as part of TravelTimes v8.1.0. It works exactly as designed: users schedule alerts for their commute routes, and every morning they get a notification with current travel data before they've even reached for their phone.

That's what building with Claude Code looks like. Not magic. Just fast, precise, production-quality software engineering.

Want to discuss AI-powered development or share your own experiences with Claude Code? Find me on LinkedIn or check out more articles at vinny.dev.

Share this post

Related Posts

Building StillView 3.0: Raising the Quality Bar with Claude Code and Opus 4.5

Using Claude Code and Opus 4.5 as thinking partners helped me rebuild confidence, clarity, and quality in a growing macOS codebase.

The New Abstraction Layer: AI, Agents, and the Leverage Moving Up the Stack

Andrej Karpathy put words to something many engineers are quietly feeling right now. We've been handed a powerful alien tool with no manual, and we're all learning how to use it in real time.

The Year Ahead in AI, Enterprise Software, and the Future of Work

From generative AI as a tool to AI as a strategic partner. Reflections on 2025 and what excites me most about 2026.